Parenting In The PDA Mirror

Parenting in the PDA Mirror: Raising Jack and Max as a PDA Autistic Mom

If you had told me years ago that one day I’d be parenting not one, but two PDA Autistic children, and doing so as a PDA Autistic adult myself, I wouldn’t have believed you. Not because it didn’t make sense (it makes perfect sense now), but because I didn’t yet have the words. I didn’t have the language or the framework. I didn’t yet understand what PDA meant for me, or what it would one day mean for my children.

What I did have was a lifetime of feeling misunderstood. A life shaped by masking, burnout, sensory overload, and navigating demands that never quite made sense to my nervous system. I knew what it felt like to move through a world that wasn’t built for my brain, my body, or my way of being.

Then came Jack.

Then Max.

Both PDA Autistic. Both gloriously, fiercely themselves.

And suddenly, I was parenting in a mirror, seeing my own childhood reflected back at me, but this time I was the one holding the frame steady.

The Joy of Shared Understanding

There’s a particular kind of joy that comes from raising PDA Autistic children when you’re PDA Autistic yourself. It’s the joy of being understood without explanation. It’s the comfort of seeing your children light up when they’re given autonomy, when their curiosity is nurtured, and when they’re celebrated for being exactly who they are.

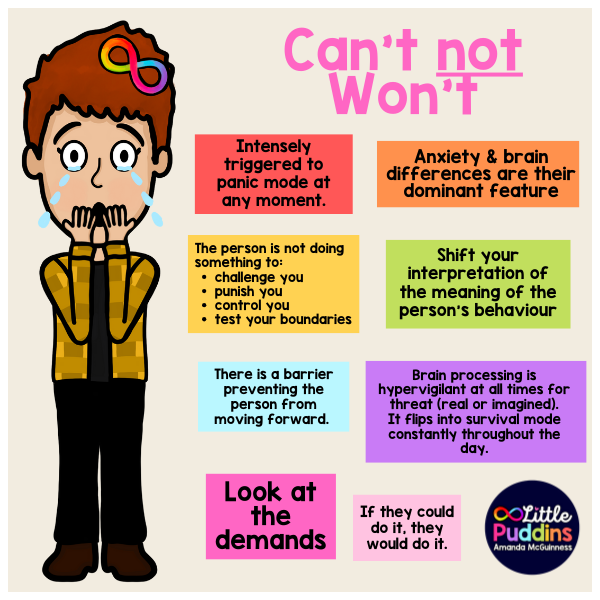

I know what it feels like to be overwhelmed by a simple question. To freeze at the sound of my name. To feel trapped by even the most well-intentioned compliments or questions. I understand the mental gymnastics of everyday life, the need for space, the craving for control over our environment, not because we’re defiant, but because our threat response, need it for survival.

In that shared understanding, there’s connection. There’s laughter. There’s creativity and chaos, often in the same breath. We joke in scripts, we communicate in code, we move to our own rhythm, and it works. For us, it works.

The Complexity of the Dual Experience

But it’s not simple. It’s not easy.

Parenting as a PDA Autistic adult comes with a level of emotional labour and nervous system exhaustion that most can’t see. It’s managing my own burnouts and shutdowns while holding space for theirs. It’s being the safe person I needed growing up, while realising I lived through a time, growing up that being your true self was not welcomed or wanted.

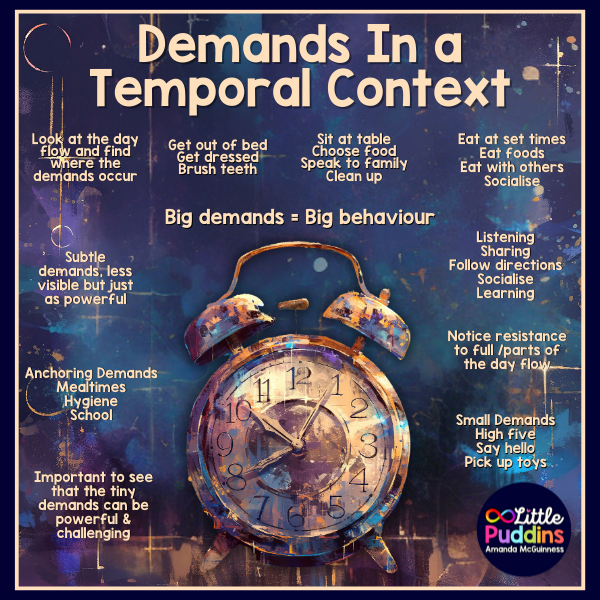

There are days when everything feels like overwhelming pressure, for all three of us.

Getting out of bed.

Making breakfast

Them needing me with them, for their own felt safety.

Me needing five minutes to breathe.

Constantly sharing my regulation, when all the while my own depletes with no time to ever fully recharge.

It’s constant negotiation, not with behaviour, but with nervous systems. With emotions. With safety.

And sometimes, I can’t meet everyone’s needs at the same time. Sometimes, all I can do is sit in the quiet with them and say, “I know. It’s a lot. I feel like that too.”

Rewriting the PDA Parenting Rulebook

Our life doesn’t follow the scripts of conventional parenting. We don’t use star charts or timeouts or “tough love.” We use connection, not correction. Trust, not compliance. Presence, not punishment.

We live by rhythm, not routine.

Some days are filled with the tiniest wins that feel like the biggest victories.

A new food tasted.

A boundary respected.

A meltdown gently supported.

Other days are about survival. About just getting through.

But always, always, there is love. There is understanding. There is this silent thread of connection that runs between us that says, “I see you. I get it. You’re not alone.”

Reparenting Myself as I Parent Them

In raising Jack and Max, I’ve come face to face with the parts of myself I never got to honour as a child. Parts that were labelled difficult, oppositional, too sensitive, too much.

Parenting them has become a form of reparenting myself.

It’s giving them the space I desperately needed.

The answers as to why I found school at times so difficult I dropped out for two years as a teenager.

The validation I didn’t know I needed.

And in doing that, I’ve started to heal parts of me I didn’t even realise were still hurting.

A Daily Act of Love, and a Daily Act of Revolution

Parenting PDA Autistic children as a PDA Autistic parent is not just an act of love. It’s an act of revolution. Of choosing to do things differently. Of refusing to force square pegs into round holes. Of creating a home where Autistic nervous systems are not only understood, but respected and honoured.

PDA Parenting

Jack and Max are not my reflection. They are entirely their own people. But in them, I see a glimpse of who I might have been if I had been raised in the modern accepting, world I’m trying to create for them.

And I’ll keep showing up, even on the hardest days, so they’ll never have to doubt that there is a place in this world for exactly who they are.

PDA References

Supporting Autistic PDA Students References:

Christie, P., Duncan, M., Fidler, R. and Healy, Z. (2012). Understanding Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome in Children: A Guide for Parents, Teachers and Other Professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Fidler, R. and Christie, P. (2019). Collaborative Approaches to Learning for Pupils with PDA: Strategies for Education Professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Truman, C. (2021). The Teacher’s Introduction to Pathological Demand Avoidance: Essential Strategies for the Classroom. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Fricker, E. (2021). The Family Experience of PDA: An Illustrated Guide to Pathological Demand Avoidance. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Cat, S. (2018). Pathological Demand Avoidance Explained. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Eaton, J. (2017). A Guide to Mental Health Issues in Girls and Young Women on the Autism Spectrum: Diagnosis, Intervention and Family Support. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Newson, E. (2003). Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome: A Necessary Distinction within the Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88(7), pp. 595–600.

Get in Touch: Contact Amanda

Follow for Insights: Instagram @littlepuddins.ie